As parents seek to engage their high school-age children in early discussions about their ambitions for pursuing a higher education – including at traditionally four-year institutions, as well as community colleges – we recommend they consider using a simple, decidedly low-tech device to begin recording their initial thinking: an old-fashioned index card.

In our book, The College Conversation: A Practical Companion for Parent to Guide Their Children Along the Path to Higher Education, Eric J. Furda, the former dean of admissions of the University of Pennsylvania, and I provide more than a dozen exercises and activities for families to undertake together. In the first, we suggest using a handful of index cards – whether 3×5, 4×6 or any other size of your choosing – to help you and your child to begin the process of looking inward at the specific attributes of a college or university experience and environment that might have the most appeal.

Index card exercise for you and your teen

For this first exercise, you and your teen might each grab a card and sit apart from each other, with the expectation that you will come back together to compare notes and to see where your respective visions for the ideal college experience align and diverge. Assuming your child is game, provide them with a series of instructions drawn from the suggestions that follow but adapted for your child’s own personality and priorities.

Remind them that their card should reflect their ideas and acknowledge that the college experience is ultimately theirs, not yours. If despite your prodding they’re resistant, this will still be a worthy process for you to engage in alone, or perhaps with a spouse or other partner, as it will provide you with valuable insights into your own thinking, with the possibility that you may be able to coax your child to the table at another time.

On your card, spend a few minutes writing a handful of words and phrases that describe the college environment that you believe might best suit your child. Don’t cite the names of individual schools or describe a school in a way that is so specific that its identity is obvious. There will be opportunities later in your extended conversation for you to share with your child particular institutions that you feel could be a good fit.

What we’re advocating here as a starting point is reducing the college experience to its barest essentials. Is there a particular subject (or subjects) that your child might enjoy studying? How about a particular setting—rural, urban, or something in between? Is athletics, varsity or intramural, a priority?

You might also consider a few attributes that are less tangible: Do you see your child as thriving in a college environment with a lot of energy, which could be inherent in the size of the institution, such as on a big football Saturday? Or will your child thrive in a less frenzied setting, as is typical on a smaller campus? Be aware that there are many schools that fall between these extremes, and that your child could well thrive in a range of environments.

Finally, identify any aspects of the college process that could be a source of anxiety. For example, if you have concerns about your child’s prospects for admission, particularly at a highly selective institution, as well as your family’s ability to pay for that education, include that.

The point of this exercise is to lay the groundwork for a mature conversation that may involve some discomfort but provide a beneficial amount of transparency.

At this initial stage, don’t overthink things. Free-associate a bit, with the goal of coming up with a half dozen partially formed ideas. This is the roughest of rough drafts, and it will undergo any number of rewrites over time. But keep these cards close by, to the point that they become dog-eared as you test your initial assumptions throughout all phases of the College Conversation.

For those who are doing this exercise on the earlier side of the admissions process, such as during your child’s sophomore year of high school, take a broader, more flexible approach, as you’ll be refining your initial thoughts multiple times over the next few years. But if it’s the fall of your child’s senior year of high school, by necessity you’ll have to be more focused and precise, as time is now of the essence.

For the purposes of this discussion, let’s assume your child has been willing to play along with the exercise. After you’ve each retreated to your respective corners for five minutes or so, come back together, exchange cards, and spend some time reviewing and reflecting on what the other has written. If both parents or another adult is involved, this could be a three-way exchange.

A good way to begin a dialogue is by identifying areas in which you concur, such as if you both agree that an optimal distance from home ranges from a one-hour to a four-hour drive. But what about those topics where you and your child are not in agreement, whether it’s an intended major or an anxiety you or they have? This is not the time to craft solutions or seek to forge common ground, as the mere raising of these issues—perhaps for the first time in your relationship—is the objective at this point. Take note of each other’s thinking—the goal at this early stage is simply to notice, to listen, and to begin to learn.

Be mindful of topics that might trigger strong emotions, whether yours or your child’s. Your preference may be for a campus less than a few hours’ drive from home, while your child dreams of being a continent away. Take note of your child’s body language and expressions. If they are retreating inward or obviously anxious, don’t press the issue but reassure them that discomfort in such discussions is natural, and essential to growth, and that you are in this together.

Before you bring your conversation to a close, highlight for your child the various points that you’ll be likely to return to in future talks, as they’ll become more important as your child begins to assemble a college list and then sets out to learn more about these institutions.

One last bit of advice: Work with your teen (and your partner or spouse, as appropriate) to establish some basic guardrails and boundaries that will govern how and when you engage in the College Conversation, as well as when you should take a breather.

If another adult is taking part in the conversation, you both might establish your own rules of engagement. Whether that person is a spouse (married or divorced), step-parent, grandparent, or family friend, spend some time thinking about how you will work together in support of your child. This may involve setting up a division of labor—is one of you, for example, more comfortable with research or logistics?

You should also agree upon ways of managing the differences and disagreements that are inevitable in a process like this. To the extent that you and another adult have different points of view, you might want to consider how to convey them to your child in the most constructive way.

We consider these broader rules of the road important enough that it is probably worth your writing them down or tapping them into a computer so that they can serve as a reference.

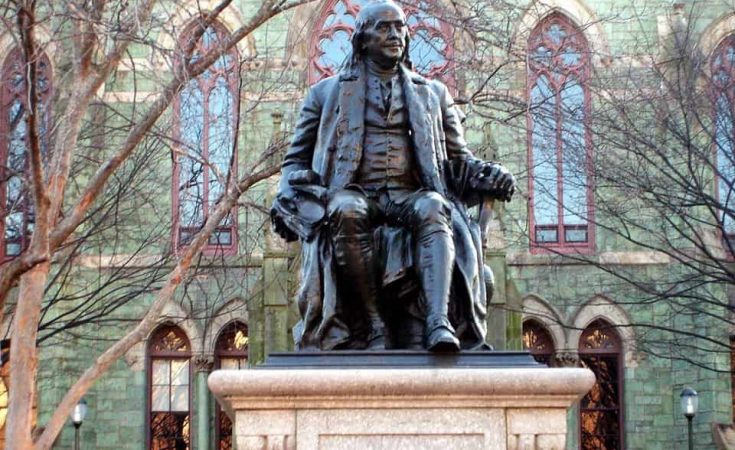

Eric J. Furda is the former dean of admissions at the University of Pennsylvania and the former executive director of admissions at Columbia University.

Jacques Steinberg is the New York Times bestselling author of The Gatekeepers and You Are an Ironman, and is a former New York Times education journalist. He has served as a senior executive at Say Yes to Education and is on the board of the National Association for College Admission Counseling. He appears periodically as a college admissions expert on NBC’s Today show.