In a recent study posted to the medRxiv* preprint server, researchers from the United States assess the incidence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) breakthrough cases and reinfections among unvaccinated and vaccinated individuals.

Study: Time to reinfection and vaccine breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections: a retrospective cohort study. Image Credit: PhotobyTawat / Shutterstock.com

Introduction

To date, SARS-CoV-2, which is the virus responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has infected over 411 million people and claimed over 5.81 million lives worldwide. In an effort to control the spread and mortality caused by COVID-19, vaccines were developed at an unprecedented pace and administered across the world. As of February 14, 2022, over 10.19 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been distributed around the world.

In particular, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccines developed against SARS-CoV-2 significantly helped control the pandemic, reduce severe outcomes, and save lives. According to the United States of America Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the risk of infection, hospitalization, and death rates are extremely high among unvaccinated people as compared to fully vaccinated individuals.

Despite the success of these vaccines, their efficacy was limited following the emergence and subsequent dominance of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant in most parts of the world. To this end, reports of breakthrough infections, hospitalizations, and death among the vaccinated individuals rose.

Aside from the protection elicited from vaccines, unvaccinated individuals who had recovered from COVID-19 experienced some level of immunity against reinfection.

Considering various spatiotemporal variables, the present study examines the incidence of COVID-19 post-vaccination in the western U.S. from December 12, 2020, to November 5, 2021, during which the Delta variant was the dominant circulating strain. Herein, the researchers also studied the reinfection rate among unvaccinated individuals to assess the protection offered by infection-induced immunity.

About the study

The researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study using electronic data from the Providence-St. Joseph Health (PSJH), is a community health system with hospitals and clinics spanning five states in the western U.S., including Alaska, California, Montana, Oregon, and Washington. The mRNA vaccines included in this study were the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 and Moderna mRNA-1273 vaccines, as well as the adenoviral vectored vaccine, JNJ-78436735 (Janssen).

Vaccine-induced and infection-induced immunity was studied from individuals across the five states. The two outcomes that were assessed in this study included breakthrough infections among the vaccine-induced immunity cohort and reinfections among the infection-induced immunity cohort. Both outcomes were confirmed through a positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase-chain-reaction (PCR) test result.

Study findings

Of the total 2,627,914 patients eligible as to be included in the vaccine-induced immunity cohort, 51.4% received two doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine, 41.4% received two doses of mRNA-1273, and 7.2% received one dose of JNJ-78436735. This cohort mostly included people between the ages of 18 and 44 years, a majority of whom were females, non-Hispanic/Latino, White/Caucasian, and California residents.

Among the fully vaccinated, 0.36% tested positive, most of whom were between the ages of 18-44 years old and had received their vaccine in the first quarter of 2021. Nonetheless, all three vaccines protected the individuals in the vaccinated cohort with a high probability of survival against breakthrough infections.

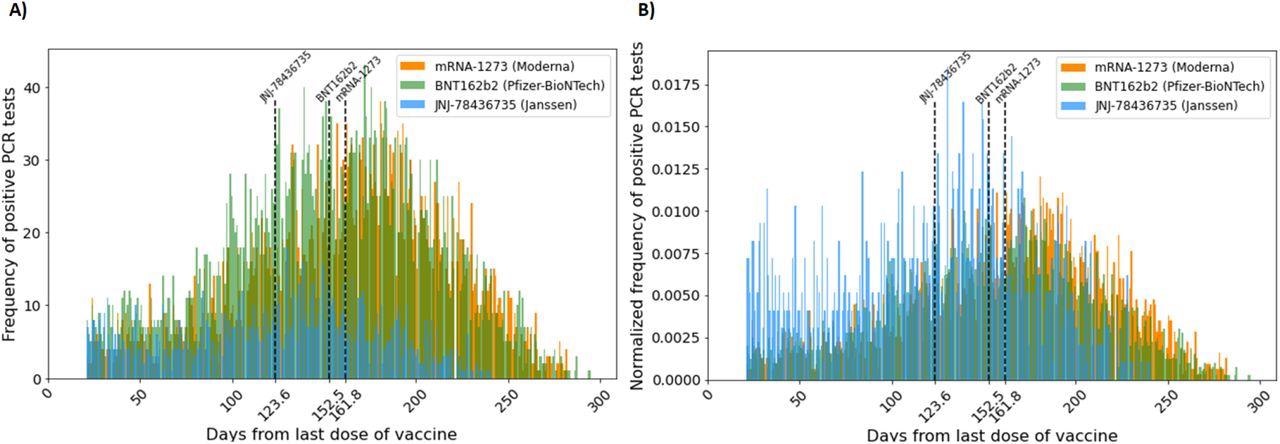

(A) Frequency of vaccine breakthrough infection (count per day) starting 21 days after the administration of the last COVID-19 vaccine dose. (B) Normalized frequency of vaccine breakthrough infection (define) starting 21 days after the administration of the last COVID-19 vaccine. Normalized frequency distributions of mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 vaccine breakthrough cases are approximately distributed normally with the mean at 161.8 days and 152.8 days, respectively. That of JNJ-78436735 vaccine breakthrough cases is skewed to the right with the mean at 123.6 days. The lines represent the mean days until breakthrough for each vaccine.

The time distribution of these vaccines showed that two doses of mRNA-1273 were the most effective, while a single dose of JNJ-78436735 was the least effective. The expected duration of time until breakthrough cases in the population for the JNJ-7843735, BNT162b2, and mRNA-1273 vaccines was 130, 155, and 168 median days to breakthrough cases respectively.

The researchers also examined the acquired immunity from a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection by characterizing the reinfection rate in this cohort of unvaccinated people. Like the vaccinated cohort, a majority of these individuals were between the ages of 18 and 44 years, female, and identified as non-Hispanic/Latino White/Caucasian.

Among the 64,424 individuals in the unvaccinated cohort, 0.88% were reinfected with SARS-CoV-2, 17.18% had not undergone another COVID-19 diagnostic test during the study period, and the remaining 81.5% did not experience SARS-CoV-2 reinfection during the study period.

One interesting observation was that there was a significantly greater number of patients with comorbidities who were vaccinated as compared to those with comorbidities who were in the unvaccinated cohort. Since comorbidities are considered as a high-risk factor for severe COVID-19, it is likely that people with comorbidities were more inclined to get vaccinated population.

Taken together, the incidence rate of reinfection was found to be higher in the infection-induced immunity cohort at 0.9% than that of the vaccine-induced cohort at 0.4%. Although this finding is smaller than what has been described in previous reports, where a six-fold higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection among the COVID-induced immunity was observed as compared to that of the vaccine-induced immunity, several other factors may influence these findings. Some possible confounding factors include geographic location, vaccines, variants, demographics, and pandemic time window, all of which may affect the rate of reinfections among both vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals.

(A) Kaplan-Meier estimates for the survival function for infection-induced immunity. Reinfection is defined by a positive COVID-19 PCR or NAAT test 90 days after the previous positive test. Range for the X axis extends to 600+ days, but only 350 days is displayed for controlled comparison with the vaccinated cohort (y-axis[0,1]). (B) More detailed close-up view of A, (y-axis[0.98,1]) (C) Kaplan-Meier estimates for the survival function restricted to patients who have been reinfected. ∼5% of reinfected patients had more than 350 days between infections. (D) Normalized frequency of reinfection 9 months after the first infection.

Limitations

The current study is not a direct comparison between the protection offered by vaccines and natural immunity, as it is difficult to establish the recovery time required for infection-induced immunity. Furthermore, because the current study was conducted in a defined period, it is possible for people to experience breakthrough infections at later times, which would skew the data distribution.

The reinfection timepoint cannot be precisely determined as actual reinfection and not an unusually long lingering initial infection. To this end, the researchers have chosen a conservative threshold of 90 days after the first positive test to determine the reinfection cases. Moreover, they added that their data is limited due to incongruencies in vaccine rollout between the three vaccines.

Taken together, the researchers call for further analyses including alternative data sources, as well as sequencing, titer levels, and other deep immunophenotyping data.

Conclusions

The current study presented demographic information, survival functions, and probability distributions for a large sample of patients experiencing vaccination breakthrough infections or post-infection reinfection within the PSJH network.

All three BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and JNJ-78436735 vaccines were found to render a very low risk of a breakthrough infection in real-world settings over 350 days.

Importantly, the current study reaffirmed that the risks associated with COVID-19 are enormously greater than any marginal advantages acquired by prior infection.

*Important notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

![(A) Kaplan-Meier estimates for the survival function for infection-induced immunity. Reinfection is defined by a positive COVID-19 PCR or NAAT test 90 days after the previous positive test. Range for the X axis extends to 600+ days, but only 350 days is displayed for controlled comparison with the vaccinated cohort (y-axis[0,1]). (B) More detailed close-up view of A, (y-axis[0.98,1]) (C) Kaplan-Meier estimates for the survival function restricted to patients who have been reinfected. ∼5% of reinfected patients had more than 350 days between infections. (D) Normalized frequency of reinfection 9 months after the first infection.](https://d2jx2rerrg6sh3.cloudfront.net/images/news/ImageForNews_704346_16448057109564821.jpg)