When Lisa LuGullo, who lives in Calgary, was pregnant with her third baby, she knew she wanted to try for a VBAC—a vaginal birth after Caesarian—and her doctor agreed that it was a good choice. After a relatively straightforward vaginal birth with her first child, LoGullo ended up with an emergency C-section with her second. “I much preferred the vaginal delivery because the recovery was so much easier,” she says. “Plus, I enjoyed the process of actually being in labour and having it all unfold with my husband and sister there.”

More and more evidence shows that VBACs are a safe option for the majority of people who have had C-sections before. And yet they’re declining in popularity across Canada: In 1995/96, 35 percent of births after a C-section were vaginal, and in 2015/16, only 19 percent of them were.

That’s mostly because of an incorrect belief that vaginal births after Caesarian are risky, says Leslie Po, an OB/GYN at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto. “There’s a misconception that you can’t have vaginal delivery after a C-section, but about 90 per cent of people who’ve had one C-section are eligible for it,” says Po. In fact, recently updated guidelines from the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada go so far as to recommend them over a planned Caesarian for those who are considered good candidates.

Here’s what you need to know about VBACs.

What is a VBAC?

A VBAC is when someone who’s had a C-section before gives birth vaginally in a subsequent pregnancy. You might hear your doctor or midwife call it TOLAC, which stands for “trial of labour after Caesarian.” This encompasses the fact that the decision is really whether to try to give birth vaginally, not whether you achieve it. “I prefer TOLAC because it describes the process rather than the outcome,” says Anna Meuser, a midwife in Mississauga, Ont., and chair of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee at the Association of Ontario Midwives.

Why are VBACs favoured by docs and midwives?

The key benefit of a VBAC is that it avoids the risks that come with any Caesarian. “Even though a C-section is a common surgery, and it’s generally safe, any surgery comes with risks,” says Meuser. Those include blood loss, infection in the incision and complications from the surgery, like injuries to the bladder and other organs. Also, babies who are birthed vaginally are less likely to have breathing issues, which are typically mild but occasionally do require time in the NICU.

A vaginal birth also saves you from the intense recovery a C-section requires. “Anytime I would cough, laugh or sneeze, the cut would hurt,” remembers LoGullo. You’ll spend less time at the hospital recovering, and have less pain, says Meuser, adding that it can also be easier to establish breastfeeding after a vaginal birth because you can breastfeed right away. This is because the hormones beneficial to breastfeeding, like oxytocin and prolactin, are released in greater quantities during and after giving birth vaginally, Meuser says. With a Caesarian, milk production may be delayed—although many people have no issues w it h breast feeding after a C-section. You might also find it easier to position the baby more comfortably when feeding following a vaginal delivery.

Having a VBAC also reduces the chances of problems with future pregnancies. The most serious is the risk that future placentas will attach to scar tissue from the C-section, a condition called placenta accreta, which can cause severe hemorrhaging after birth. “The more C-sections you have, the more the risk of those placental problems increases. For people planning on having more children, this can be important,” says Meuser.

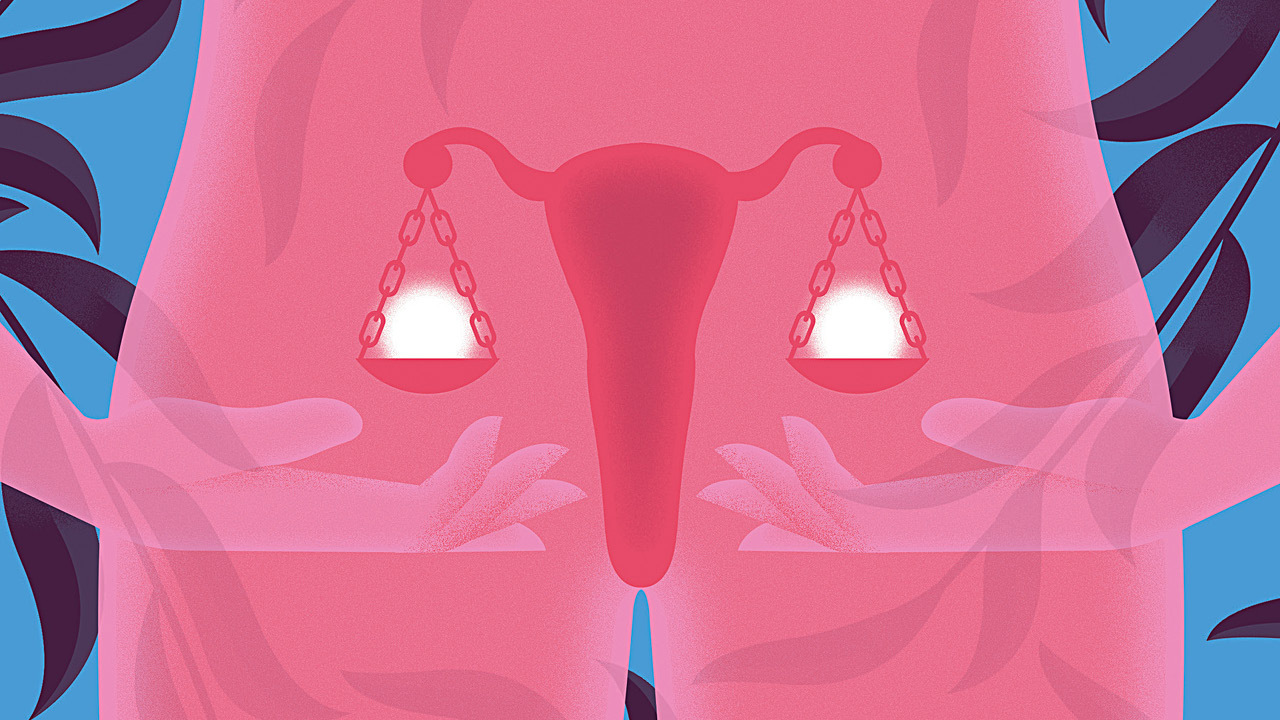

Illustration: Neil Webb

Are there any risks associated with VBACs?

The main risk of a VBAC is a uterine rupture which is when the scar inside the uterus from the previous C-section tears, due to the uterus expanding and contracting during labour. “If that scar opens up while you’re labouring, it can have very significant consequences,” says Po. One is blood loss, which can be serious enough to require a blood transfusion. Another is an injury to an organ, like the bladder.

There are also risks to the baby: A uterine tear can cause the placenta to detach, which can lead to oxygen deprivation or even death. And while the risks to the baby in a VBAC are higher than they are in an elective or planned C-section, they’re still rare. There’s a one-in-200 chance of uterine rupture, and if that happens, there’s a three-in-10,000 chance of fetal loss, says Po.

Doctors will work to mitigate the risks, though. Inducing labour can contribute to uterine rupture because the uterus contracts more than it would during spontaneous labour. So if you’re having a VBAC, your doctor or midwife won’t use certain types of medicine to get labour going. Instead, they might use a Foley catheter balloon, which stretches the cervix rather than using contractions to dilate it, says Po. To avoid an induction, your doctor or midwife may try to jump-start things using a stretch and sweep, where they use their fingers to separate the amniotic sac from the cervix. You can also choose to book a C-section that you would opt for if you don’t go into labour spontaneously.

The bottom line is, a VBAC that ends in a vaginal birth is the safest option for both mother and baby, a planned C-section is the second safest and a VBAC that ends in an unplanned C-section is the least safe. That’s because when the C-section is done in an emergency—for example, due to concerns about the baby’s heart rate—the procedure happens faster, which can lead to trouble, says Po. “Complications can arise, whereas in a planned C-section, there is plenty of time to organize and perform the surgery in a more controlled manner.”

What is the VBAC success rate?

VBACs end in a vaginal birth about 75 percent of the time. Interestingly, the success rate is largely based on things that happened before you even got pregnant.

For example, have a peek at your C-section scar. Those with a low horizontal cut tend to be well-suited for vaginal birth, while those with a T-shaped incision or a classical incision (a vertical cut higher up, near the belly button) aren’t, because those incisions are more likely to rupture. Don’t worry if you don’t know what kind you have—your doc will look at the report from your previous C-section to confirm your incision type. Both classical and T-shaped incisions are rare these days, says Meuser.

Beyond that, a good candidate is somebody who has had at least 18 months between deliveries and who has had only one C-section, says Po. Being younger, having a BMI under 30 and not having high blood pressure each also increases the chances of an attempted VBAC ending in a vaginal birth.

The other thing doctors and midwives consider is the reason for the last C-section. If it was because the baby was breech, or there were concerns about the baby’s heart rate, it’s more likely that a VBAC will work, says Po. If it was because labour wasn’t progressing well or it didn’t start spontaneously, it’s more likely that those problems might repeat themselves and a VBAC will end in a C-section.

Chat with your healthcare provider about your personal risk, and weigh it against your own preferences. “I have some patients who say, even if there’s only a 15 percent chance that things would happen vaginally, they want to try, while others say, even if there’s a 75 certain chance, they want a C-section,” says Po.

Do you need to be in a hospital for a VBAC?

It’s strongly recommended by obstetric guidelines. While there isn’t definitive research to say that a hospital birth will lead to better outcomes than a home VBAC, the recommendation makes sense to many doctors and midwives, including Meuser. That’s because the first sign of a uterine rupture is usually issues with the baby’s heart rate. During a home birth or at a birthing centre, midwives use intermittent monitoring to check the baby’s heartbeat every five to 30 minutes. But in a VBAC, continuous monitoring is recommended instead. That’s only available in hospitals, though both doctors and midwives can oversee it there.

The other reason is that TOLACs have to be done where a C-section is accessible, says Po. If things go sideways and you need an emergency C-section or a blood transfusion, being in a hospital already means you can get the help you need quickly, with no travel time. Research shows that outcomes of uterine rupture are worse when there’s a longer wait to surgery.

But it’s a myth that a specialist is required—family doctors and midwives regularly do VBACs and can stay in charge of your care throughout the birth, even if it’s in a hospital. Some midwives with extra training, like Meuser, can even assist in a C-section if that’s where a VBAC ends.

As for LoGullo, she’s glad she chose to try for a VBAC, and it worked out well for her. She gave birth with her husband and sister in the room, and was able to be home two days later, taking care of her oldest two kids without surgical recover y to contend with. “I was definitely relieved and happy,” she says. “It felt like the best way to end my birthing journey.” But had it not worked out, as planned VBACs sometimes don’t, she absolutely should not have felt like she failed, adds Meuser: “Having a repeat C-section is not at all a failure. It’s just another way to have a baby.”